The fundamental problem in meeting the energy needs of homes, industry, and artificial intelligence is the difficulty in building more generation. Reports of rising electricity prices reflect barriers to entry that make electricity artificially scarce and expensive. The key to low-cost energy that is widely accessible to all is having lots of electricity generators to serve customers.

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) is the country’s primary permitting problem and barrier to new generation. NEPA applies to “major Federal actions significantly affecting the quality of the human environment.” In practice, it covers a broad range of activities conducted, financed, permitted, or approved by federal agencies, such as building highways, approving infrastructure projects, or granting licenses for energy development.1

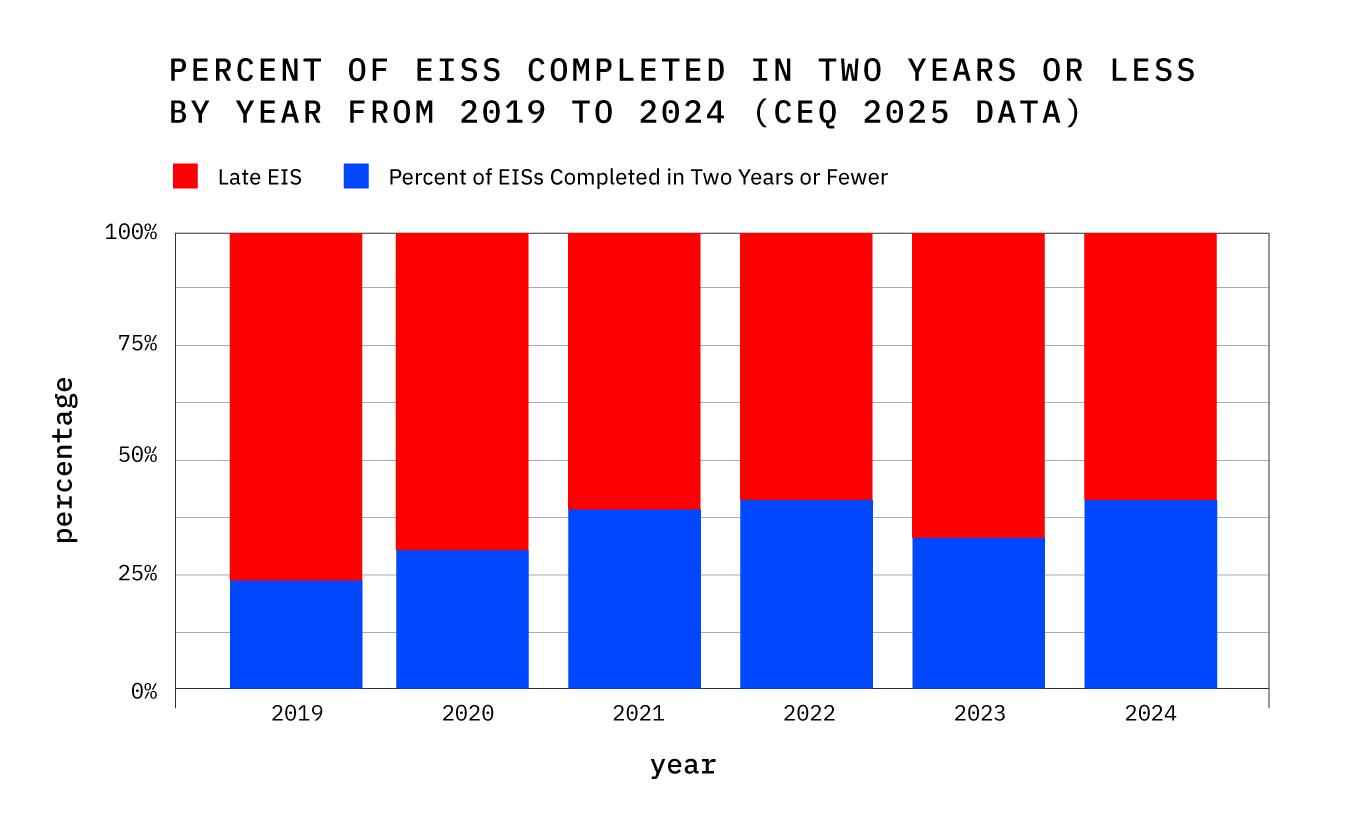

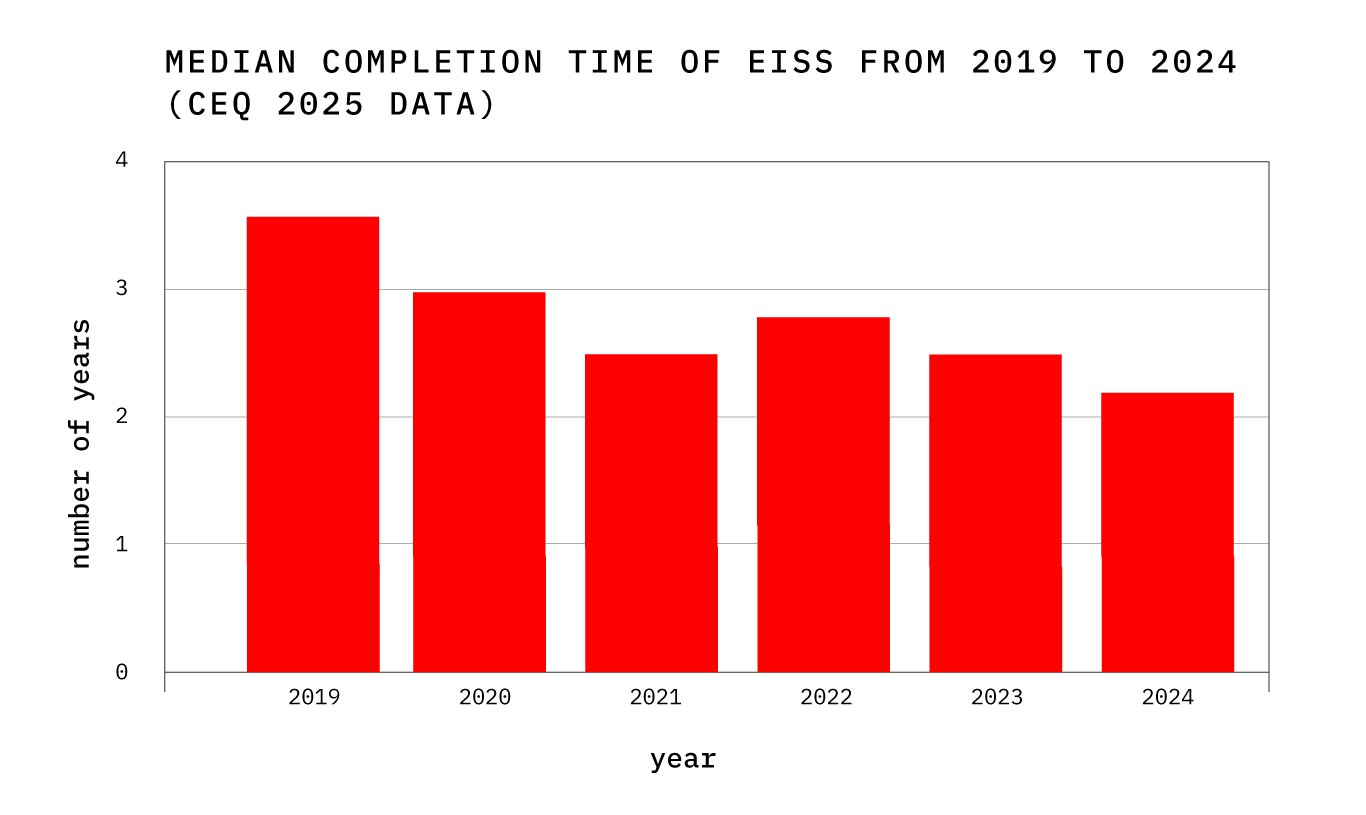

NEPA review timelines have been growing basically since the bill’s passage.2 Final EIS’s issued in 2024 took a median of 2.2 years and an average of 3.8 years.3 In addition to years of time, these reviews are thousands of pages long.4 Recent timelines may have declined a small amount because of the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023’s permitting changes. Yet almost two out of three projects are still late, according to a 2025 government agency’s report.5 There is clearly still room for continued improvement.

Even as these length and time requirements grow, they also demonstrate that NEPA is toothless. A project that identifies every possible harm it could create moves forward no matter what those harms are because NEPA is only a procedural requirement rather than a substantive protection for Americans.

Reform is both necessary and possible. It’s possible because permitting reform has long been a bipartisan effort. Presidents Clinton, Bush, Obama, Biden, and Trump have all recognized that long reviews have frustrated their policy goals. As this suggests, wind, solar, pipelines, and roads all fall prey to NEPA’s litigation doom loop.6

There are a wide range of effective permitting reform options for policymakers today. They range from the most aggressive to more incremental improvements:

- Deleting NEPA entirely and replacing it with substantive protections.

- Requiring that permitting agencies consider only the direct, proximate, and reasonably foreseeable effects of federal actions.

- Exempting more regular actions from reviews and expanding categorical exemptions.

- Shortening the statute of limitations for NEPA to be 180 days (at most) instead of the six years currently in statute.

- Allowing injunctive relief only in rare cases where (1) they are brought promptly, (2) by parties with direct and preexisting connections to the action’s effects, and (3) where there are risks of imminent and substantial environmental harm, and there is no other equitable remedy available as a matter of law.

- Making the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission the lead agency in environmental reviews of transmission projects and extending categorical exclusions to transmission projects.

- Directing agencies to develop procedures and reforms that allow swift leasing and use of federal lands for all types of energy and mineral development and production.

If Congress enacts rules like these, it will reduce energy costs for the entire country. In addition, wide areas of federal lands, especially areas of the western United States, will open for energy development and related mineral development.

1 Eli Dourado, “Much More than You Ever Wanted to Know about NEPA,” The Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University, October 20, 2022, https://www.thecgo.org/benchmark/much-more-than-you-ever-wanted-to-know-about-nepa/.

2 Josh T. Smith and Eli Dourado, “Update to the Regulations Implementing the Procedural Provisions of the National Environmental Policy Act,” The Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University, March 10, 2020, https://www.thecgo.org/research/update-to-the-regulations-implementing-the-procedural-provisions-of-the-national-environmental-policy-act/.

3 “Environmental Impact Statement Timelines (2010-2024),” Council on Environmental Quality, January 13, 2025, https://ceq.doe.gov/nepa-practice/eis-timelines.html.

4 Jennifer Morales and Steffen Rigby, “NEPA Timelines for Clean Energy Projects: Understanding Delays in Clean Energy Development,” The Center for Growth and Opportunity, March 12, 2025, https://www.thecgo.org/research/nepa-timelines-for-clean-energy-projects-understanding-delays-in-clean-energy-development/.

5 The CEQ report indicates that averages may be skewed by certain projects that take much longer. “Environmental Impact Statement Timelines (2010-2024).”

6 James W Coleman and Arnab Datta, “We Must End the Litigation Doom Loop | IFP,” Institute for Progress, May 29, 2024, https://ifp.org/we-must-end-the-litigation-doom-loop/.