Testimony before the House Subcommittee on the Administrative State, Regulatory Reform, and Antitrust of the Committee on the Judiciary

Hearing: Artificial Intelligence: Examining Trends in Innovation and Competition

Thank you, Chairman Fitzgerald, Ranking Member Nadler, and subcommittee members for having me here today to talk about the vibrant innovation and competition in the AI ecosystem. I am Neil Chilson, the Head of AI Policy at the Abundance Institute.

The Abundance Institute is a mission-driven nonprofit dedicated to creating the cultural and policy environment necessary for emerging technologies to germinate, develop, and thrive, and to thereby perpetually expand widespread human prosperity and abundance.

The current wave of advanced computing technologies, commonly referred to as “artificial intelligence,” have the potential to create enormous economic growth and human flourishing across the United States. The U.S. leads the world in this technology – in innovation, products, companies, and investment.

It is true that there are important challenges ahead to continued U.S. leadership in AI.1 But a lack of AI competition is not one of them.

Indeed, the complex AI ecosystem is vibrant and competitive. The biggest threat to this vibrant competition is overregulation. Existing regulation and threats of regulation hamper disruptive companies and penalize innovation. Policymakers can best expand competition in the AI ecosystem by clearing old regulatory barriers and resisting the impulse to raise new ones.

AI isn’t a Market or an Industry–It is a Complex Ecosystem

AI is a general purpose technology – perhaps the most general purpose technology – meaning that AI has applications in all industries.2 AI will thus shape competition within every industry where it is applied. Often these applications will decentralize and enhance competition. For example, as increasingly powerful generative AI tools lower the barriers to creating high-quality content, expect smaller teams to better compete with larger, more-resourced incumbents.3 Market conditions or government interventions that reduce the availability of AI tools will limit this pro-competitive effect across industries.

However, most discussion among competition analysts has focused on analyzing competition within the AI “industry.” Even ignoring the broad application of AI, such analysis is challenging. Artificial intelligence tools are a complex stack of technologies. For example, an AI-powered smartphone application may use an application programming interface (API) to connect to an OpenAI ChatGPT instance running on a Microsoft Azure cloud service that is powered by custom networked computers using Nvidia hardware. Some AI company offerings span layers; others are more limited.

Each layer of the stack has a novel economic structure. For example, foundational models, as software, have significant returns to scale. Once trained they can be deployed many times, for many different uses, and the marginal user adds little additional cost. In contrast, the computational infrastructure – chips, computing clusters, even data centers – have more limited returns to scale due to the cost of manufacturing physical components.4

Additional complexity comes from the fact that interventions or market changes to one of these layers has ripple effects across other layers. For example,

“[A] lack of competition at the infrastructure layer would certainly affect AI foundation models, but the agents at the layer of those models would respond by investing in infrastructures. This dynamic is already in play. OpenAI is reportedly trying to raise $7 trillion to develop its own chips and computing power. Aware of this risk, Nvidia is pushing to steadily lower the cost of training LLMs, from $10 million a few months ago to as little as $400,000…”5

Simple competition analysis might separate layers of the AI stack into different markets, but any analysis that fails to consider these cross-layer currents would be incomplete.

Finally, the path of AI technology continues to evolve, and its direction and speed is difficult to predict. For example, the recent trend is that models continue to gain capabilities primarily through scaling the number of parameters, driving continuously increasing demands for data and compute. But there is some evidence that scaling could fail to provide corresponding returns.6 An AI ecosystem without perpetual improvement through scaling looks very different, from a competition perspective, from one where scaling continues to return outsized value.

The AI Ecosystem is Vibrant and Competitive

The artificial intelligence industry spans a broad technology stack – from the hardware that power AI computations to the end-user applications delivering AI-driven experiences. Across each layer of this stack, there is intense competition and rapid innovation. The United States and China lead in many areas of AI, backed by massive investments and vibrant ecosystems, while Europe, Israel, India, and others also contribute notable players and innovations.

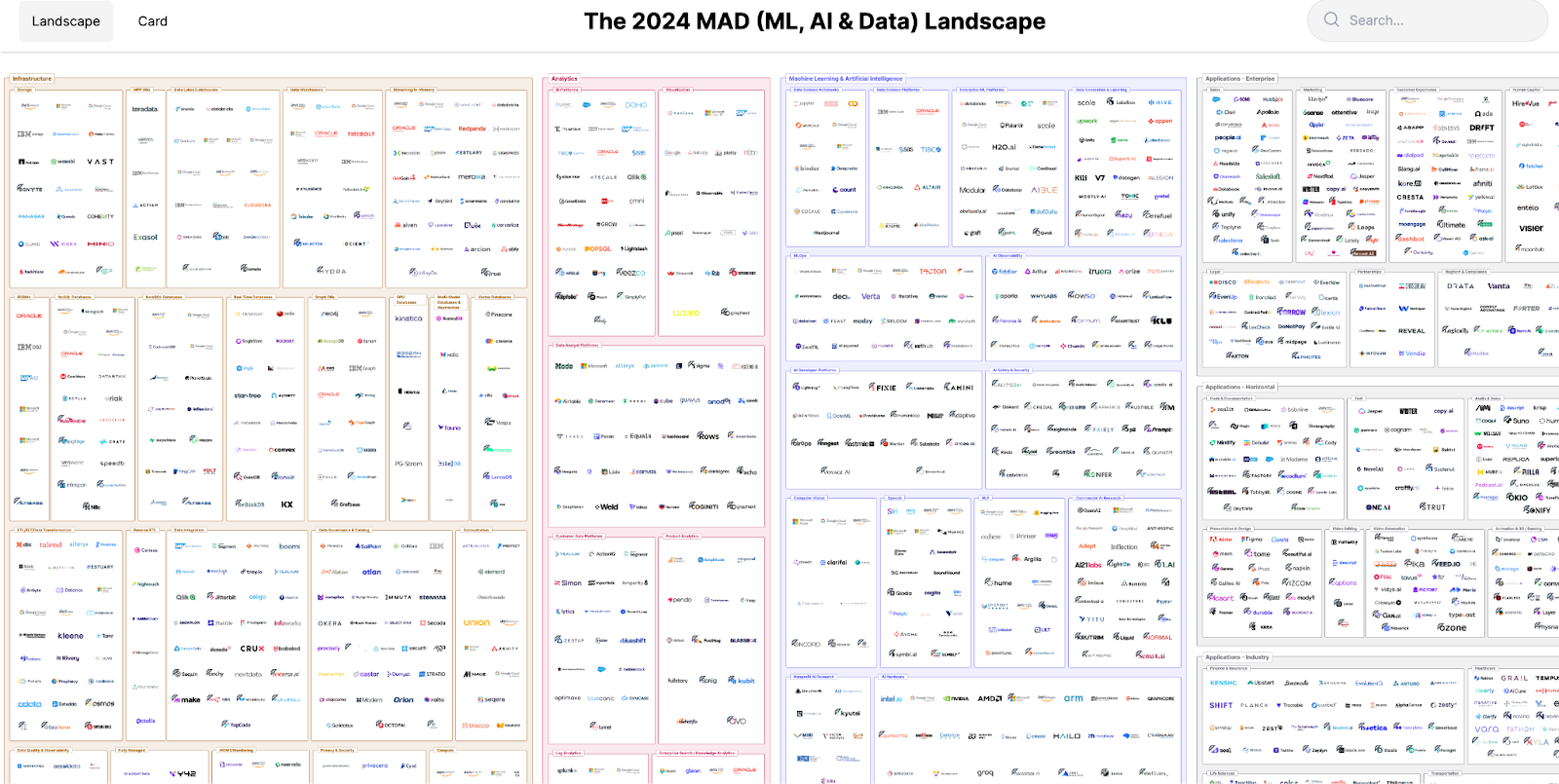

The result is one of the most dynamic, rapidly evolving tech ecosystems in human history. FirstMark’s 2024 Machine Learning, AI & Data Landscape features 2,011 different company logos, “with 578 new entrants to the map” since the 2023 version, grouped into nine major categories and 100 subcategories.7

Across all layers of the AI stack – hardware, cloud, models, tools, and applications – competition is robust and global. In hardware, one player (Nvidia) leads but is challenged by a long list of rivals (AMD, Intel, Google TPU, startups, Chinese chipmakers), resulting in rapid performance gains and new chip innovations.8 In cloud infrastructure, three U.S. giants compete neck-and-neck while Chinese and other providers, including startups, also compete, driving down prices for compute and motivating new AI-focused services.9 At the model level, we’ve moved from a world of a few landmark models to dozens of cutting-edge models by many organizations, with open-source efforts ensuring broad dissemination of AI capabilities.10

The past 10 years have seen exponential growth in AI capabilities and usage, driven by competitive dynamics. The number of AI startups, the amount of training compute used, and the size of models all grew by one or more orders of magnitude in the last decade. For example, compute used in landmark AI trainings doubled every 6 months on average from 2012–2018 – an astonishing pace – reflecting how each breakthrough (AlexNet, then GPT, then GPT-2, etc.) spurred others to quickly outdo it.11 New entrants frequently disrupt incumbents, perhaps best seen with OpenAI’s ChatGPT catching the largest tech companies in the world by surprise, but also more recently with DeepSeek’s releases, forcing continual adaptation. Market share shifts in cloud (AWS down from 33% to 30% while Azure/Google Cloud rose) and framework usage (TensorFlow to PyTorch swing12) exemplify how competition prevents stagnation.

Quantitatively, the AI ecosystem is large and fast-growing, with no signs of winner-take-all dynamics. Nvidia’s dominance in GPUs is the result of being the first and most innovative foundational hardware that facilitated deep learning advances, and the company is running hard to stay ahead of AMD, Google, Amazon, and Chinese players that are investing billions to erode that lead.13 In cloud, the leading provider has only ~30% share and has lost a few points as others (including startups like CoreWeave14) grow – a healthy market with fierce R&D and price competition.15 In the application layer, the number of companies is immense and growing fast, with 1,812 new AI startups funded globally last year.16 The AI enterprise services market is highly fragmented, as the top firm, Accenture, holds just 7% in genAI services.17 Funding and innovation indicators are equally strong: $131.5 billion in VC funding for AI startups in 2024, which is fueling new competitors in every niche of AI.18 Meanwhile, AI adoption in enterprises is growing rapidly, with 78% of companies reporting use in at least one business function – up from 55% in 2022.19 And AI is projected to contribute trillions to economic output in coming years, suggesting plenty of opportunity for many players.20

Competition is driving innovation and democratization. Thanks to competitive pressures, AI capabilities that were cutting-edge a few years ago are now widely accessible. For instance, state-of-the-art image generation (which once required specialized knowledge and expensive compute) is now available for free to anyone via open-source tools (e.g. Stable Diffusion). Enterprise AI services have become pay-as-you-go utilities on cloud. The fact that 11 different developers globally achieved GPT-4-level models in 2024indicates no one can rest on their laurels.21 Driving that point home recently, the Chinese company DeepSeek rocked the ecosystem by delivering powerful frontier models developed with uniquely efficient algorithms.22 We’re also seeing lower costs: the cost to train an image classifier or language model has plummeted, and AI API prices continue to fall, often announced in tandem with competitor launches.23 This vibrancy, however, also raises the bar. Companies must continue investing heavily to stay in the game (as seen by multi-billion dollar AI R&D budgets of tech firms). This arms race nature is producing a continuous stream of AI innovations benefiting consumers, from more accurate translations to safer autonomous vehicles.

In short, the AI industry is characterized by dynamic competition at every layer, primarily led by U.S. and Chinese organizations but with meaningful contributions from around the world. Quantitative indicators – market shares that shift year to year, exponential growth in investment and output, and the proliferation of new entrants – all illustrate a vibrant ecosystem rather than a static market. For policymakers, this suggests that the current trajectory of AI is one of rapid innovation fueled by competition. Nurturing this competitive environment will be key to maintaining the U.S.’s edge and ensuring the benefits of AI are widely distributed. In summary, the state of the AI industry is one of intense but healthy competition – a positive sign that this technology space is far from ossified and will continue to deliver breakthroughs and economic value in the years ahead.

Open Source is a Key Vector of AI Competition

Open source software has long enabled competition in software generally. As I and my co-author noted in comments to the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, this is also true in the artificial intelligence ecosystem.24 Open model weights25 benefit competition in the marketplace for AI services and in other areas of the economy in many ways, including:

- Leveling the playing field: Open models reduce the barriers to entry and give smaller players and startups access to cutting-edge AI technology. This could increase competition across the economy as more organizations are able to leverage powerful AI capabilities in their products and services without needing the massive resources to develop the foundational models themselves. This leveling effect is supported by research that demonstrates that using generative AI tools in work settings disproportionately benefits lower-performing workers.26

- Shifting focus to applications and fine-tuning: With shared access to strong open models, competitive differentiation will depend on how well companies can adapt and apply the models to specific domains and use cases. The ability to efficiently fine-tune models and develop powerful applications on top of them could become more important than the ability and capacity to train a foundational model from scratch.

- Commoditization of foundational models: In the long run, open models could commoditize foundational AI technology. If everyone has access to high-quality open models, the models themselves may not be a sustainable competitive advantage. The real value may migrate to compute, proprietary datasets, customizations, and application-specific IP. This would distribute gains from this technology more broadly across the economy.

- New business models: Open models could spur new business models and ways of creating value in the AI ecosystem. For example, there may be opportunities to provide compute resources for fine-tuning, offer managed services around open models, or develop proprietary add-ons and extensions.

- Collaboration and shared standards: Open models could foster greater collaboration and interoperability within the AI community. Shared standards and a common technological substrate could emerge, enabling more vibrant competition in the application layer.

The primary implication of all these points is that open models do and will increase competition at the model layer, spurring innovation at that layer and distributing value creation to other layers of the AI stack. Decisionmakers across the political spectrum have recognized the pro-competition and pro-innovation benefits of open-source AI.27 Congress likewise should support open source as a powerful avenue of AI competition and innovation.

There is a Threat to AI Competition: Overregulation

While the AI ecosystem is robust in competition, there is a threat to this vibrant environment: overregulation.

The negative impact of regulation on competition is well established. George J. Stigler’s foundational work, “The Theory of Economic Regulation,” demonstrates how industry regulations, far from safeguarding consumers, often serve the interests of established businesses by creating barriers to entry.28 Stigler argues that regulation frequently results from incumbent firms exerting political influence to shape rules that limit market access for potential competitors, thereby solidifying their market dominance. Consequently, regulatory policies intended to promote consumer welfare or economic fairness can paradoxically entrench monopolistic behavior, reduce incentives for innovation, and ultimately harm consumer interests through higher prices and limited choices.

Compliance costs associated with regulation can further impede competition by disproportionately burdening smaller or newer firms that lack the resources of established competitors. High compliance expenses—including legal, administrative, and technological requirements—may create significant barriers to entry, preventing potential competitors from entering the market or scaling effectively. Consequently, incumbent firms with greater financial strength and regulatory expertise gain a competitive advantage, further entrenching their market dominance.

When ChatGPT launched in November 2022, the federal response to amazing U.S. AI leadership should have been celebratory and supportive. Instead, the Biden administration’s dour reaction set the U.S. AI ecosystem on the wrong path toward less innovation and less competition. President Biden issued an unprecedented Executive Order that emphasized the potential risks of the technology and kicked off dozens of regulatory actions.29 Motivated by concerns over potential harms, Biden sought to corral the biggest players into a soft standard-setting cabal that would have disadvantaged smaller companies and future disruptors.30

Meanwhile, Biden competition agencies met the entire ecosystem with skepticism. FTC Chair Lina Khan, for example, began signaling concern as early as March 2023, when she emphasized that large-scale machine learning requires “huge amounts of data … and storage” and warned that incumbent tech firms could use their vast resources and market power to “squelch[] rivals.”31 In subsequent speeches and forums, Khan repeatedly claimed signs of potential market concentration around essential AI inputs (like GPUs and cloud infrastructure), cautioning that dominant platforms might exploit these “bottlenecks” through coercive contracts or unfair pricing.32 The FTC’s first competition-related post on AI after the release of ChatGPT said nothing about the obvious disruptive procompetitive effects of the new technology; instead, it ran through a laundry list of potential competitive harms that might emerge in the space.33 By early 2024, the FTC’s skepticism had coalesced into a formal inquiry via 6(b) orders, compelling major industry players—including Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Anthropic, Microsoft, and OpenAI—to disclose details on their AI investments and alliances.34

President Trump swept away the Biden AI Executive Order promptly after entering office.35 And his administration has reframed the entire federal conversation around AI from one based in fear to one based in opportunity. As Vice President J.D. Vance recently said in a speech at the Paris AI Summit, “[W]e believe that excessive regulation of the AI sector could kill a transformative industry just as it’s taking off, and we will make every effort to encourage pro-growth AI policies.”36

Unfortunately, the U.S. is still at risk of wrapping the AI industry in regulatory red tape, hurting both competition within the U.S. and our national competitiveness with other countries. More than nine hundred bills regulating AI have been introduced in state houses across the country since this year’s legislative sessions began.37 These bills would impose a wide, and sometimes conflicting, range of requirements. They range from helpful and targeted on state-related concerns to broad and onerous extraterritorial regulation. These state AI bills, while usually well-intentioned, do not help or may actively undermine the ability of the U.S. to capitalize on the promise of AI.

And in any case, a patchwork of parochial regulation threatens competition. As mentioned above, complex and conflicting legal requirements mean high compliance costs that only the largest players can afford.

In addition to the general anti-competitive effect of many kinds of regulation, some types of regulation harm AI competition. For example, given the critical role of open source and open weight AI research, regulatory restrictions that limit or disincentivize the development or distribution of open-source AI or open weight models can be expected to harm competition. Furthermore, overly restrictive data regulation limits the collection of useful information, again favoring incumbents with substantial amounts of data. Finally, copyright structures (which are themselves a form of government-granted monopoly) that undermine constitutionally protected fair use again deter model developers without deep pockets. Any serious evaluation of how to promote competition in AI must consider how legal and regulatory constraints affect such competition.

Finally, some existing or expected artificial barriers to vibrant AI competition are international. Some regions – the European Union in particular – have adopted laws with intentionally global effect and have historically demonstrated an enforcement focus on U.S. companies.38 Such actions should be seen as protectionist and potentially anticompetitive, and the U.S. government should use its diplomatic and trade authority to preserve vibrant competition in AI.

What Congress Can Do to Spur AI Competition

To enhance the competitive environment for AI innovation and maintain U.S. global leadership, Congress should act decisively. The following recommendations focus specifically on creating a competitive environment that attracts investment, stimulates innovation, and encourages new market entrants:39

- Preempt Restrictive State AI Regulations: Congress should enact federal preemption of restrictive state-level AI regulations. By creating a consistent national regulatory landscape, innovators and entrepreneurs would face fewer barriers to entry, stimulating competition and fostering market dynamism.

- Establish Negative Liability Protections: Congress should establish negative liability laws limiting the exposure of general-purpose AI model developers to legal risks stemming from third-party misuse. Reducing disproportionate litigation risks will encourage more companies, including startups, to enter the AI market and innovate without fear of prohibitive legal consequences.

- Create Safe Harbor Provisions: Safe harbor laws clearly defining minimal, innovation-friendly compliance practices will significantly lower the barriers for new and smaller players in the AI space. Clear standards enable emerging competitors to innovate confidently, leveling the playing field with established companies.

- Codify the Right to Compute: By establishing a robust right to compute, Congress can prevent overly restrictive governmental actions against computational resources. Protecting this right ensures that new competitors and smaller businesses can access essential technological resources without burdensome regulatory barriers, fostering greater competition.

- Clarify Liability Frameworks: Congress should clearly differentiate liability between foundational AI model developers and specific deployers of AI applications. A clear liability framework reduces uncertainty, encouraging new entrants by ensuring that liability risks are predictable and manageable, thereby invigorating competition.

- Accelerate Data Availability for AI Training: Mandating the release and digitization of unstructured federal datasets will democratize access to valuable training data. Improved access to data reduces the advantage of large incumbents, enabling smaller firms and startups to innovate more effectively and compete more vigorously in the AI market.

These legislative initiatives will collectively foster an environment of robust innovation, further enhancing America’s AI competitiveness and reinforcing its global leadership in artificial intelligence.

Conclusion

In sum, the U.S. AI ecosystem is a dynamic and highly competitive environment, with new entrants and established players driving innovation at every layer of the tech stack. This vibrant competition creates broader access to AI tools and spurs continual advancements that benefit consumers, businesses, and society at large. Yet this promising trajectory is threatened by overregulation—particularly complex, overlapping, and heavy-handed legal regimes that impose outsized burdens on smaller players and stifle open-source innovation. To sustain robust competition, encourage disruptive breakthroughs, and maintain U.S. leadership in AI, policymakers should adopt a light-touch regulatory approach, clear regulatory barriers to competition, and remain vigilant against foreign protectionist measures. By doing so, America can preserve the competitive dynamism of AI and continue reaping its economic and societal benefits for years to come.

1See Neil Chilson, Building the Launchpad for an AI Moonshot, Testimony Before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Subcommittee on Economic Growth, Energy Policy, and Regulatory Affairs (April 1, 2025); Neil Chilson and Josh Smith, Comment on Request for Information on the Development of an Artificial Intelligence Action Plan (March 2025), https://abundance.institute/articles/development-of-an-AI-action-plan.

2 There is no consensus definition of “artificial intelligence.” See, Neil Chilson, Testimony Before the United States Senate Committee on Rules and Administration, Hearing: AI and the Future of our Elections at 2 (Sept. 27 2023), https://www.rules.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/chilson_testimony.pdf. Most people use the term colloquially and in a very broad sense; this breadth is another challenge for competition analysis.

3See, e.g., AI’s impact on law firms of every size (Aug. 15, 2023),https://legal.thomsonreuters.com/blog/ais-impact-on-law-firms-of-every-size/ (describing how solo practitioners and small law firms can use AI to take on new types of matters while large firms “wait on committees or consultants to approve an AI approach.”).

4See, Thibault Schrepel, Toward A Working Theory of Ecosystems in Antitrust Law: The Role of Complexity Science, Dynamics of Generative AI (ed. Thibault Schrepel & Volker Stocker), Network Law Review, Winter 2023, https://www.networklawreview.org/schrepel-ecosystems-ai/ (“The infrastructure layer does not directly benefit from strong increasing returns (i.e., there are scale economies limited by the costs of components), but it interacts with the foundation layer, which does.”).

5Id.

6 Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor, AI Scaling Myths (June 27, 2024), https://www.aisnakeoil.com/p/ai-scaling-myths.

7 Matt Turck, Full Steam Ahead: The 2024 MAD (Machine Learning, AI & Data) Landscape (Mar. 31, 2024), https://mattturck.com/MAD2024/.

8 Joaquin Fernandez, The Leading Generative AI Companies (March 4, 2024), https://iot-analytics.com/leading-generative-ai-companies/.

9 Swagath Bandhakavi, Cloud infrastructure market reaches $330bn in 2024, driven by GenAI growth (February 7, 2025), https://www.techmonitor.ai/hardware/cloud/cloud-infrastructure-market-330bn-2024-genai-growth; Mark Haranas, AWS, Microsoft, Google Fight for $90B Q4 2024 Cloud Market Share (February 13, 2025), https://www.crn.com/news/cloud/2025/aws-microsoft-google-fight-for-90b-q4-2024-cloud-market-share.

10 Robi Rahman, Lovis Heindrich, David Owen, Luke Frymire, Over 20 AI models have been trained at the scale of GPT-4 (January 3-, 2025), Epoch AI, https://epoch.ai/data-insights/models-over-1e25-flop; Baidu CEO says more than 70 large AI language models released in China (September 5, 2023), Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/technology/baidu-ceo-says-more-than-70-large-ai-language-models-released-china-2023-09-05/.

11 Veronika Samborska, Scaling up: how increasing inputs has made artificial intelligence more capable (January 19, 2025), Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/scaling-up-ai.

12 Eli Uriegas, Meta and Jennifer Bly, PyTorch Foundation, PyTorch Grows as the Dominant Open Source Framework for AI and ML: 2024 Year in Review (December 23, 2024), PyTorch, https://pytorch.org/blog/2024-year-in-review/.

13 Joaquin Fernandez, The Leading Generative AI Companies (March 4, 2024), https://iot-analytics.com/leading-generative-ai-companies/.

14 Mark Haranas, AWS, Microsoft, Google Fight for $90B Q4 2024 Cloud Market Share (February 13, 2025), https://www.crn.com/news/cloud/2025/aws-microsoft-google-fight-for-90b-q4-2024-cloud-market-share.

15 Swagath Bandhakavi, Cloud infrastructure market reaches $330bn in 2024, driven by GenAI growth (February 7, 2025), https://www.techmonitor.ai/hardware/cloud/cloud-infrastructure-market-330bn-2024-genai-growth.

16 Vanessa Parli, Raymond Perrault, Erik Brynjolfsson, et al, The AI Index 2024 Annual Report, page 245 (2024), https://hai.stanford.edu/ai-index/2024-ai-index-report.

17 Joaquin Fernandez, The Leading Generative AI Companies (March 4, 2024), https://iot-analytics.com/leading-generative-ai-companies/.

18Alex Irwin-Hunt, AI dominates venture capital funding in 2024 (January 8, 2025), https://www.fdiintelligence.com/content/41641e67-f00f-53c0-97cb-464b3a883062.

19 Alex Singla, Alexander Sukharevsky, Lareina Yee, and Michael Chui, The state of AI: How organizations are rewiring to capture value (March 12, 2025), QuantumBlack AI by McKinsey,https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/the-state-of-ai#:~:text=McKinsey_Website_Accessibility%40mckinsey.com-,AI%20use%20continues%20to%20climb,-Reported%20use%20of.

20 Lapo Fioretti, Carla La Croce, Andrea Siviero, Elisabeth Clemmons, The Global Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Economy and Jobs: AI Will Steer 3.5% of GDP in 2030. (August 2024), IDC, https://www.idc.com/getdoc.jsp?containerId=prUS52600524.

21 Robi Rahman, Lovis Heindrich, David Owen, Luke Frymire, Over 20 AI models have been trained at the scale of GPT-4 (January 3-, 2025), Epoch AI, https://epoch.ai/data-insights/models-over-1e25-flop.

22 Eduardo Baptista, What is DeepSeek and why is it disrupting the AI sector? (January 28, 2025), Reuters, https://www.reuters.com/technology/artificial-intelligence/what-is-deepseek-why-is-it-disrupting-ai-sector-2025-01-27/.

23OpenAI GPT-4 API Pricing (August 22, 2024), https://www.nebuly.com/blog/openai-gpt-4-api-pricing.

24 Neil Chilson and Logan Whitehair, Comments of the Abundance Institute on Dual Use Foundation Artificial Intelligence Models with Widely Available Model Weights (Mar. 27, 2024), available athttps://www.regulations.gov/comment/NTIA-2023-0009-0246.

25 “Open source” in the context of AI can mean many different things. For the purposes of this testimony, I am focused on foundational models with open, publicly available weights. There are similar competitive implications from other forms of openness in AI.

26 Brian Eastwood, Workers with less experience gain the most from generative AI (Jun. 26, 2023) https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/workers-less-experience-gain-most-generative-ai; Erik Brynjolfsson et al., Generative AI at Work (Oct. 9, 2023) Working Paper, https://danielle-li.github.io/assets/docs/GenerativeAIatWork.pdf.

27See FTC Staff, On Open-Weights Foundation Models (July 10, 2024), https://www.ftc.gov/policy/advocacy-research/tech-at-ftc/2024/07/open-weights-foundation-models; Lina Khan, Post on X.com, https://x.com/linakhanFTC/status/1811172503617773672; J.D. Vance, Post on X.com, https://x.com/JDVance/status/1764471399823847525.

28 George J. Stigler, The Theory of Economic Regulation, The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science Vol. 2, No. 1 Page 3-21, (1971), JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3003160.

29 Neil Chilson, Government Overreach in the Presidential Executive Order on Artificial Intelligence (March 21, 2024), testimony before the House Subcommittee on Cybersecurity, Information Technology, and Government Innovation, https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Chilson-Testimony.pdf.

30 Margaux MacColl, Why Marc Andreessen was ‘very scared’ after meeting with the Biden administration about AI (December 15, 2024), TechCrunch, https://techcrunch.com/2024/12/14/why-marc-andreessen-was-very-scared-after-meeting-with-the-biden-administration-about-ai/.

31 Adi Robertson, The US government is gearing up for an AI antitrust fight (March 28, 2023), The Verge,https://www.theverge.com/2023/3/28/23660101/ai-competition-ftc-doj-lina-khan-jonathan-kanter-antitrust-summit.

32A few key principles: An excerpt from Chair Khan’s Remarks at the January Tech Summit on AI (February 8, 2024), The Federal Trade Commission Technology Blog, https://www.ftc.gov/policy/advocacy-research/tech-at-ftc/2024/02/few-key-principles-excerpt-chair-khans-remarks-january-tech-summit-ai.

33Generative AI Raises Competition Concerns (June 29, 2023), The Federal Trade Commission Technology Blog, https://www.ftc.gov/policy/advocacy-research/tech-at-ftc/2023/06/generative-ai-raises-competition-concerns.

34 Federal Trade Commission, Press Release, FTC Launches Inquiry into Generative AI Investments and Partnerships (January 25, 2024), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2024/01/ftc-launches-inquiry-generative-ai-investments-partnerships.

35 Donald J. Trump, Executive Order 14148—Initial Rescissions of Harmful Executive Orders and Actions, 90 FR 8237(January 20, 2025), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2025/01/28/2025-01901/initial-rescissions-of-harmful-executive-orders-and-actions.

36Remarks by the Vice President at the Artificial Intelligence Action Summit in Paris, France (February 11, 2025), The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-the-vice-president-the-artificial-intelligence-action-summit-paris-france.

37 MultiState.ai, Artificial Intelligence (AI) Legislation, https://www.multistate.ai/artificial-intelligence-ai-legislation.

38 Kelvin Chan, Europe’s world-first AI rules get final approval from lawmakers. Here’s what happens next (Mar. 13, 2024) (noting that penalties could be as much as 7% of a company’s global revenue), https://apnews.com/article/ai-act-european-union-chatbots-155157e2be2e42d0f1acca33983d8c82.

39 These recommendations are based on our response to the Office of Science and Technology Policy’s Request for Comment on the Development of an Artificial Intelligence Action Plan. That document offers more detail about some of these recommendations. See Neil Chilson and Josh Smith, Comment on Request for Information on the Development of an Artificial Intelligence Action Plan (March 2025), https://abundance.institute/articles/development-of-an-AI-action-plan.